Basics of Hydrogen

Hydrogen is the smallest and lightest element and forms molecular hydrogen (H2) gas at standard pressure and temperature. It’s extremely abundant, relatively easy to synthesise from water, and has a high gravimetric energy density (energy per unit mass). For these reasons, it has a lot of potential as an energy source.

However, due to how small hydrogen is, there are several considerations and barriers to overcome regarding its storage and use:

- Embrittlement – hydrogen will permeate into metals (including steel) and reduce its ductility, causing cracks to form and eventually material failures.

- Low density – Hydrogen has a very low density, leading to a low volumetric energy density, around 3.0kWh/m3 compared to natural gas with 10.1kWh/m3.

- This means that when burning hydrogen, either the flow rate must be 3x higher than natural gas, or compression must be higher to achieve the same energy flow.

- Because of its low density, hydrogen is very commonly stored as a compressed gas or liquid. This requires specialised storage tanks, compressors, and potentially cryogenic refrigeration, making storage expensive.

- Leaks – due to its small size, hydrogen gas will more readily leak from a container compared to other gases.

Hydrogen Production

Although there are many ways to produce hydrogen, the two most common are steam reformation of fossil fuels and electrolysis. Depending on the method of production, it is given a different name:

- Grey hydrogen – produced from fossil fuels, e.g., gasification or steam reformation,

- Blue hydrogen – as grey hydrogen, but paired with carbon capture and storage,

- Green hydrogen – produced using electrolysis powered by renewable electricity.

Steam Reformation

The most common hydrogen production method is steam reformation (around 48% of all hydrogen production1), where high temperature (700+°C) and pressure (3-25 bar) steam reacts with a hydrocarbon to produce carbon dioxide and hydrogen. The cleanest and highest-yielding hydrocarbon to use is methane (steam methane reformation – SMR), because it has 4 hydrogen atoms and only 1 carbon atom. Longer hydrocarbon chains have a higher ratio of carbon to hydrogen, meaning they produce a relatively higher amount of CO2 when reformed.

Steam reformation is a mature technology and is the source for most of the pure CO2 used in the UK; H2 is used in the industrial synthesis of ammonia (NH3) for fertiliser whilst CO2 is captured and sold to food and drinks manufacturing, as well as horticulture.

The reforming reaction is as follows:

CH4 + H2O → CO + 3H2

Typically, a water-gas shift reaction is then undertaken to produce further hydrogen:

CO + H2O → CO2 + H2

Steam needs to be produced to drive steam reformation, which is normally done using natural gas combustion. In addition, methane is one of the reactants. Therefore, SMR is heavily reliant on the cost of natural gas. Small margins are often optimised through economies of scale, where larger installations are cheaper per kilogram produced compared to small installations. During the 2022 energy crisis, some of the large-scale SMR ammonia production plants in the UK ceased operations, contributing to the rise in fertiliser and pure CO2 costs.

The biggest limiting factor for small/medium-scale SMR is production efficiency, which maximises around 60% for commercially available units. This means that in producing hydrogen, 40% of the input energy is already lost. The economics therefore only make sense when both H2 and CO2 have very high value; and even then, if gas prices rise, it may be uneconomical to run without even considering the capital cost of the system.

Electrolysis

Currently making up only a small proportion of hydrogen production in the UK, electrolysis uses electricity to split water into oxygen and hydrogen. The primary benefit of electrolysis is from a carbon emissions perspective; it can remove fossil fuels from hydrogen production and, even when using grid electricity, has lower emissions. It can also be used to store excess renewable power, avoiding curtailment or sale of electricity during periods where the wholesale price is low.

An electrolysis cell comprises two electrodes: one positively (anode) and one negatively (cathode) charged terminal, separated by an electrolyte material which is conductive to charged particles. There are three main types of electrolysis reactors, differentiated by the type of electrolyte used: alkaline, proton-exchange membrane, and solid oxide.

Each type of electrolyser works in a similar way, the anode splits water into positively and negatively charged ions, e.g., hydrogen ions (H+), free electrons (e–), and oxygen (O). Free oxygen forms oxygen gas and electrons are re-added to hydrogen ions at the cathode, producing the hydrogen gas product. The overall equation is:

2H2O → 2H2 + O2

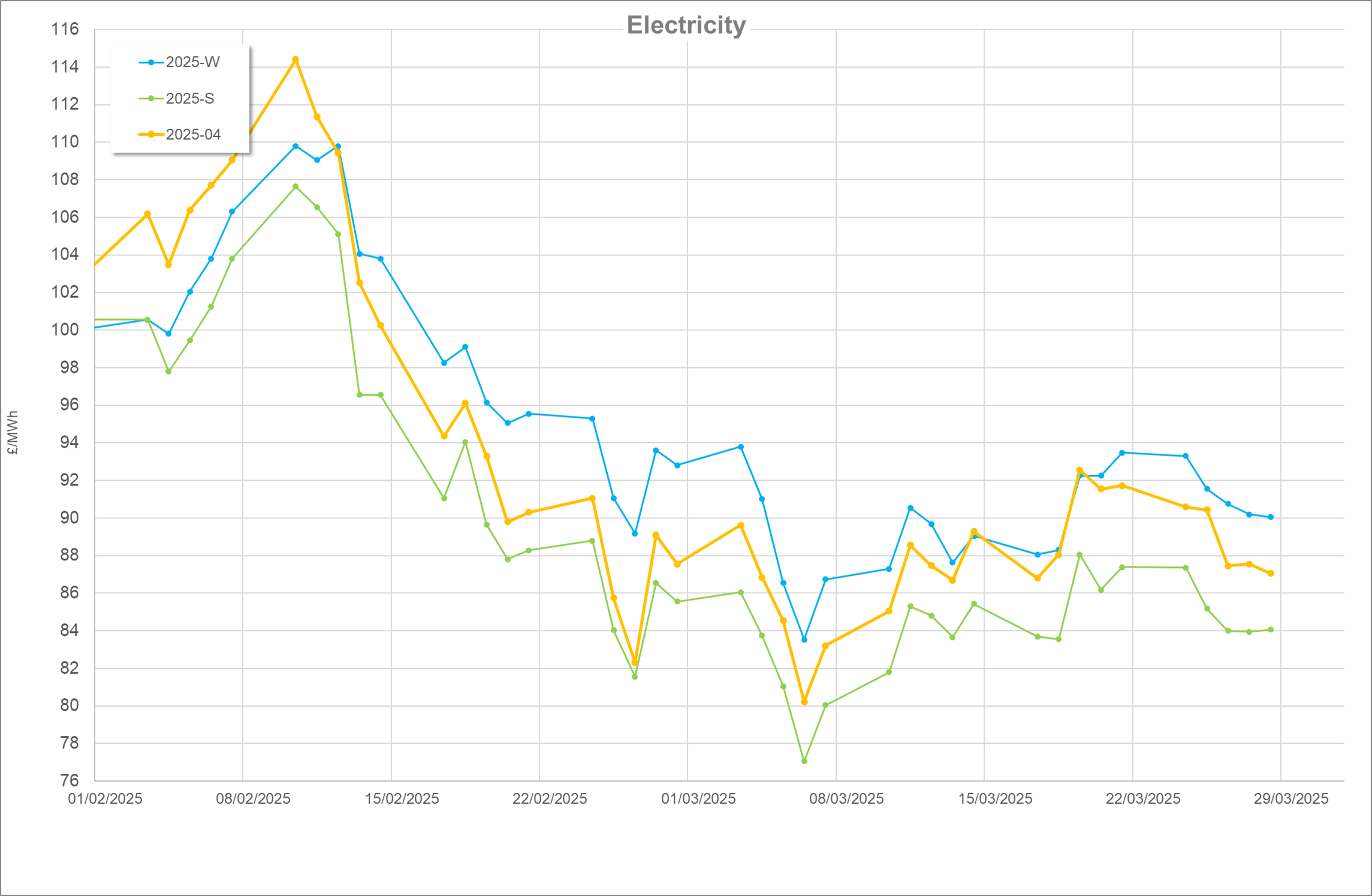

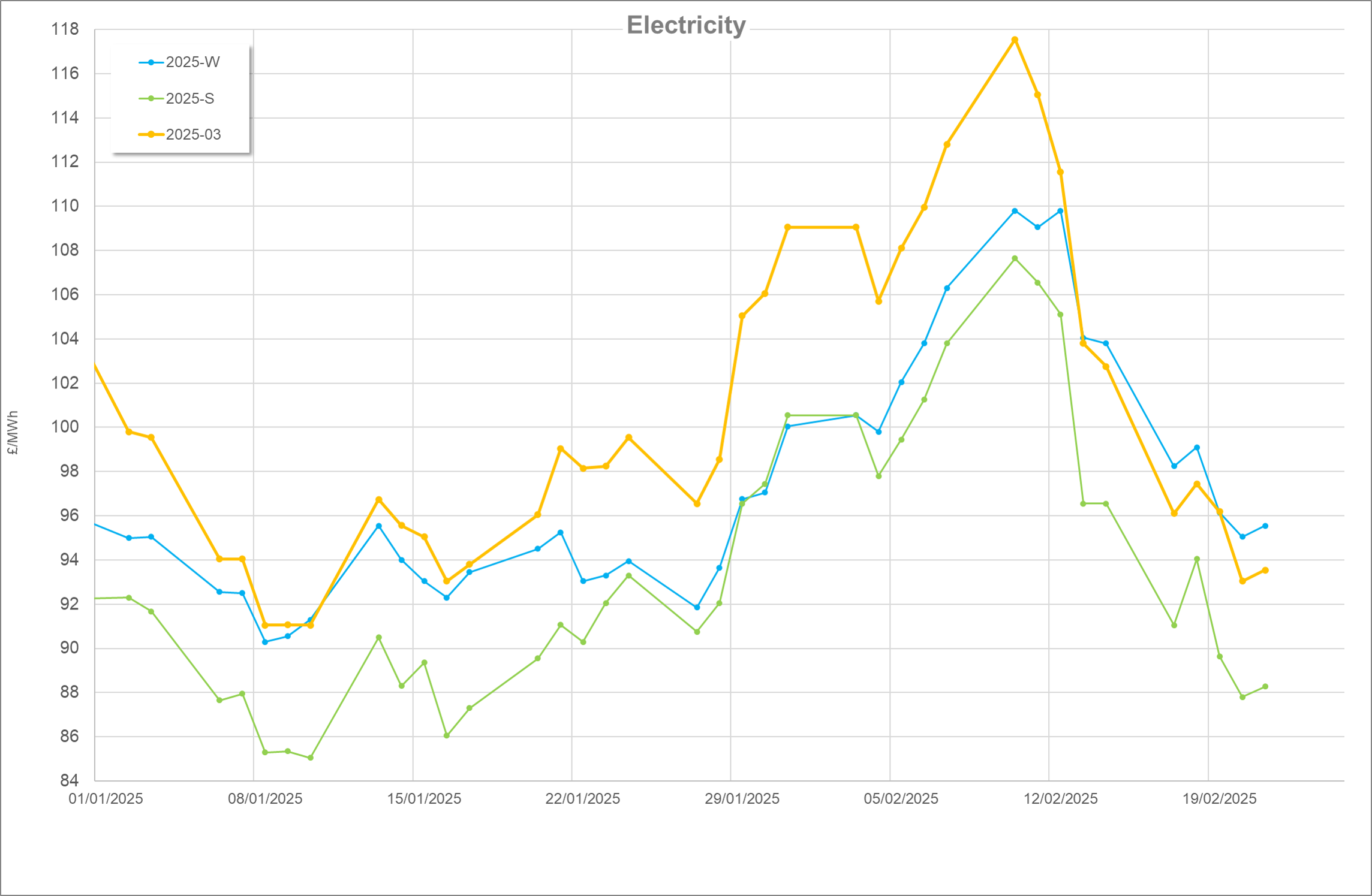

Once again, the largest barrier is production efficiency, which is slightly under 60%. Electrolysis would very rarely be operated using grid electricity due to how expensive it would be to run, leaving the main use-case as electrical storage for excess renewable power. In comparison, batteries lose only around 10% of the input energy.

Therefore, for electrolysis to make financial sense, the difference in price of electricity between times of excess production and times when hydrogen would be used for power must overcome the loss of primary energy production. Often, it will make more sense to simply export excess power and import from the grid when needed.

Use

Once hydrogen has been produced, there are two primary methods of use: combustion and fuel cells, which both lead to further loss of energy.

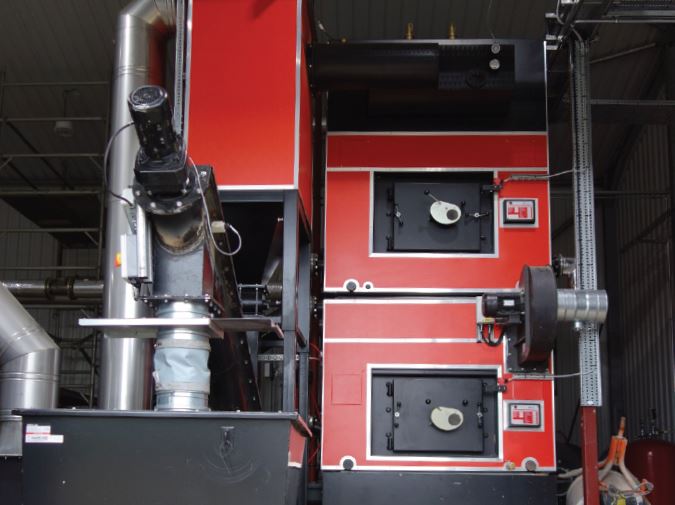

Combustion

The simplest way to get useful energy out of hydrogen gas is through combustion. Some units can burn a blend of hydrogen and natural gas, as well as pure hydrogen. Hydrogen burns much cleaner than natural gas. The primary emission is water vapour, although nitrogen oxides (NOx) can still be produced due to the combustion temperatures.

As with natural gas combustion, the combined thermal and electrical efficiencies of hydrogen CHP combustion is around 90%. Considering electricity as the primary output, as it is the most valuable, only around 27% of the input energy is finally converted to electricity.

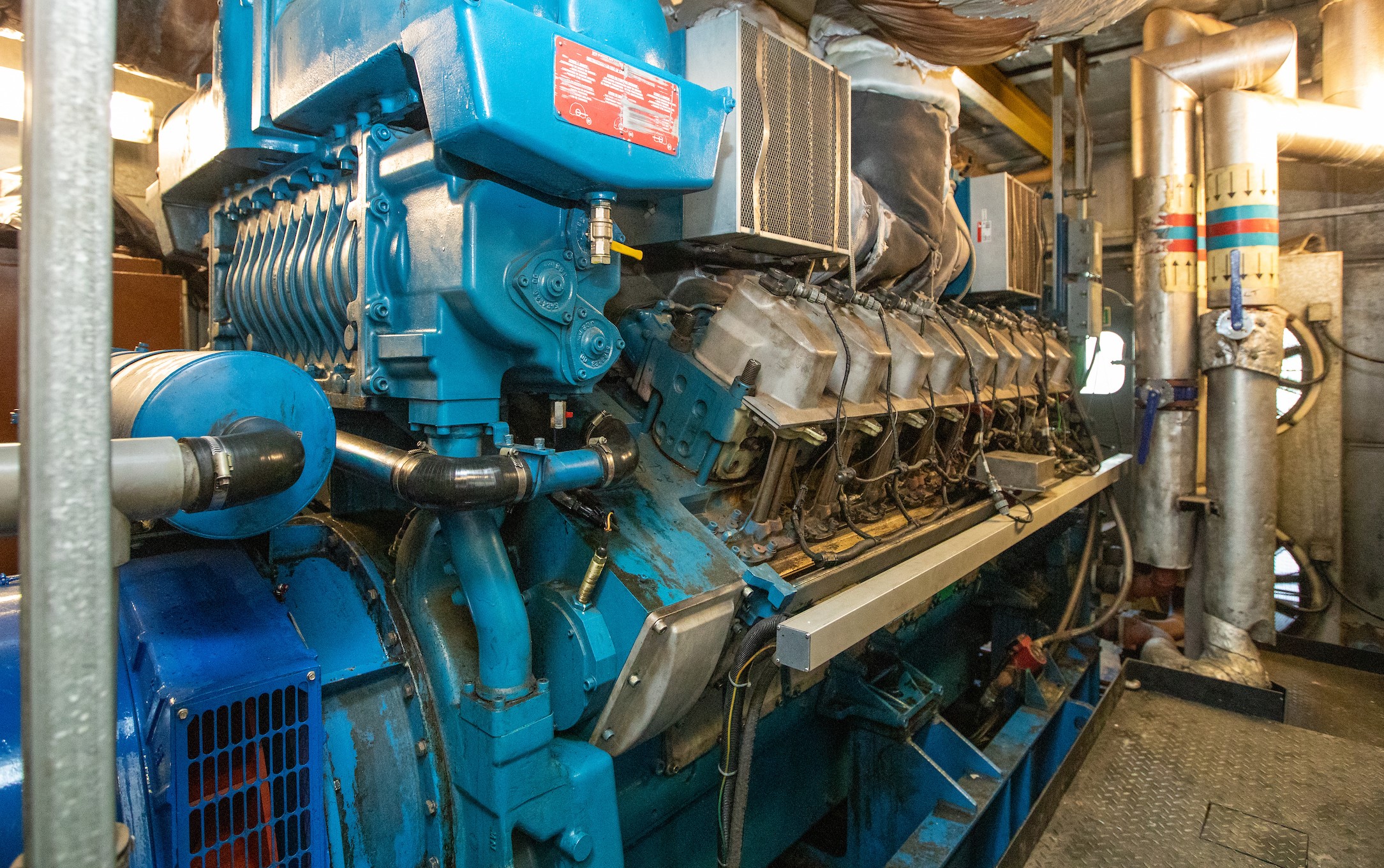

Fuel Cells

Conversely to electrolysis, fuel cells use an electrochemical reaction to generate electricity. They do this by combining hydrogen and oxygen into water, which induces a current and produces heat as a byproduct.

In principle, an electrolysis reactor can run in reverse, acting as a fuel cell. However, the most common technology (alkaline electrolysis) does not have favourable reversible characteristics in terms of temperature and catalyst use. Solid oxide reactors show the most promise for a viable system that acts as both a hydrogen generator and fuel cell CHP, however the technology is not currently ready for commercial applications2.

The outputs of fuel cells can be compared directly with gas-fired CHP. Electrical efficiency is higher, up to 65%, but combined efficiency remains at a maximum of around 90%3. This means that up to 39% of the input energy can be extracted again as electricity.

Conclusion

Given the current state of the energy market and the specifications of the commercially available hydrogen production/use equipment, the economics do not stack up without the aid of incentive schemes. There may be exceptions, e.g., when a large amount of power cannot be exported and would otherwise be curtailed. Additionally, very large-scale hydrogen production may be viable through economies of scale.

References

- Review on Techno-Economics of Hydrogen Production Using Current and Emerging Processes: Status and Perspectives. Medhat A. Nemitallah et al. Results in Engineering 21 (2024). ↩︎

- Operating Principles, Performance and Technology Readiness Levels of Reversible Solid Oxide Cells. Fiammetta Rita Bianchi and Barbara Bosio. Sustainability 13 (2021). ↩︎

- Prospects of Fuel Cell Combined Heat and Power Systems. A.G. Olabi et al. Energies 13 (2020). ↩︎

Written by Eirinn Rusbridge